-

Texas Knight

- Current Issue

- Archive

- About

- Contact

Texas Knight

Menu

Texas Knight

Menu

Vol. 2, 2024 - 2025

U.S. Army Chaplain Father Emil Kapaun died in a Korean prisoner-of-war camp 72 years ago yesterday. In the decades after the Korean War, Father Kapaun’s courage on the battlefield and selfless service to fellow POWs became legendary, leading the U.S. military to recognize him with a Medal of Honor and the Diocese of Wichita, Kansas, to open his cause for canonization. In 2021, the chaplain’s remains were finally identified and brought home — with a little help from Columbia magazine.

Ray Kapaun remembers lifting the remains of his uncle, Father Emil Kapaun, for the first time after his skeleton was positively identified in a laboratory in Honolulu, Hawaii, in 2021.

“I know he held a lot of soldiers as they died in his arms when they were on the battlefield. But here I could actually pick him up and hold him and carry him and lay him onto the gurney where he was going to go out. I never thought I would have that moment,” he told reporters.

“He has carried me for a lot of my life,” he said, “and it was the greatest honor in the world for me to be able to pick him up and carry him once.”

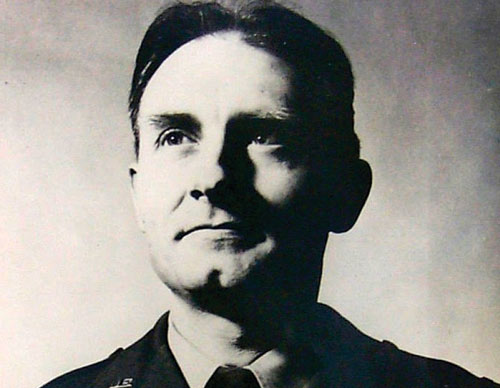

Father Emil Joseph Kapaun, a chaplain of the U.S. Army, died in a North Korean prisoner-of-war camp in 1951. For his valor on the battlefield and as a POW during the Korean War, he posthumously received the Medal of Honor in April 2013, making him one of only five 20th-century chaplains to be given the military’s highest award for valor.

In 1993, Father Kapaun was named a Servant of God, and his cause for canonization opened in 2008. The Church is now investigating miracles attributed to his intercession to determine whether he may be canonized a saint. But his family and friends feel as if they have already witnessed one miracle: the return of his remains to his home state of Kansas in September 2021, 70 years after his death.

The chances of his return home increased dramatically when a certain magazine — most likely a copy of Columbia — found its way into a medical clinic waiting room in 2003.

William Hansen was one of the prisoners Father Kapaun served in Camp 5 in North Korea, in conditions so horrific that he suffered from nightmares for decades afterward. Hansen, who worked as a bus driver in New York City before his retirement in Naples, Florida, sought relief at a Veterans Affairs medical clinic in Naples in 2003. It was in the waiting room that he saw a picture of Father Kapaun in what he later described as “a Knights of Columbus magazine” — probably the March 2003 issue of Columbia, which featured an article titled “A ‘Saint’ Among Soldiers.” It told the story of the heroic chaplain and his potential cause for canonization in the Diocese of Wichita. All of a sudden, something clicked.

“I know this man,” he told the doctor. “I buried him.”

Hansen added that he had signed an Army nondisclosure agreement never to talk about his POW experience. The doctor replied, “That was 50 years ago,” and recommended that he get in touch with the diocese.

In late November 2003, Hansen did so, making contact with Father John Hotze, who had been assigned to investigate Father Kapaun’s possible cause for canonization in 2001. The priest listened to Hansen’s story with incredulity.

“I thought, ‘This can’t be true,’” recalled Father Hotze, the current vice postulator of the cause and a longtime member of the Knights. He remembers thinking that even if Hansen believed that he recognized Father Kapaun from the magazine, likely left at the VA clinic by a local Knight, there was no way that he could have buried the chaplain. Most of the approximately 1,600 men who died in Camp 5 were buried in mass graves along the Yalu River.

Despite his doubts, Father Hotze decided to call Philip O’Brien, a senior analyst at the Defense Prisoner of War Missing Personnel Office, one of whose many tasks was to try to identify everyone who had died in Camp 5. If anyone could gauge the veracity of this tale, it was likely O’Brien, who had conducted hundreds of interviews with POWs.

After interviewing Hansen, O’Brien stunned Father Hotze by telling him, “All of this rings true.”

Hansen shared previously unknown details about how Father Kapaun died and, crucially, what happened next: In May 1951, after a brutal winter in Camp 5, the 35-year-old chaplain was taken to the camp’s dreaded “death house,” a pagoda where ill soldiers were brought and from which they almost never returned alive. Hansen was also a patient there, but he could walk and thus offer limited care for others.

Father Kapaun’s slim food ration was placed at the doorway of his sick bay, and Hansen would help the priest by bringing it to him until guards ordered him to stop.

Knowing that death was near, Father Kapaun asked to be buried away from the mass graves near the river. “Try to bury me on higher ground,” he told Hansen, “where I can still look over things.”

When Father Kapaun died, Hansen and two other prisoners were ordered to dispose of his body, supervised by a guard. Prior to the spring thaw, a dead prisoner would have been buried in a mass grave and covered with a minimal amount of dirt. By May, the ground was no longer frozen, and though the guard did not like the idea of burying Father Kapaun near the pagoda, he relented.

Father Hotze recalled Hansen telling him that “they dug down about a foot and a half, then pushed the dirt over the body and put whatever they could find on top of it to keep it safe from animals.”

Several years later, when hostilities ended and the United States arranged for the return of soldiers’ remains, the rocks and debris Hansen left alerted the Chinese to the presence of the body, which was buried well above the river’s flood plain.

Father Kapaun was one of approximately 560 Americans whose relatively intact remains were returned from Camp 5 in 1954 and brought to the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu’s Punchbowl Crater. About 70 of these soldiers, including Father Kapaun, were not identified at the time, and his remains lay there for years beneath a plaque marked “Unknown.”

For decades after his death May 23, 1951, Father Kapaun’s mother, Elizabeth, longed for her son’s body to return home. Late in life, she suffered from dementia and forgot family members’ names — but she never forgot her son, repeatedly asking if Emil was returning home until the day she died in 1986.

“No man left behind” is a sacred promise the U.S. military works tirelessly to keep. But the return of remains from North Korea has been particularly complicated, and the best efforts to retrieve and identify U.S. service members sometimes fail. Hansen helped to change that for Father Kapaun. His account of the chaplain’s burial, shared after seeing the Columbia article, confirmed what O’Brien suspected: that Father Kapaun’s body was probably in Hawaii, not among the commingled, fragmented remains that North Korea had begun returning from mass graves in 1990. It gave renewed impetus and focus to the effort to identify Father Kapaun among the interred unknowns.

This the military laboratory did March 4, 2021 — with “100% certainty,” matching not only the skeleton’s DNA, but also its teeth, height and age.

Later that year, Father Kapaun’s nephew, Ray, traveled to Honolulu to reclaim his remains. As a teenager in the 1970s, Ray hadn’t appreciated his uncle’s story until he read the 1954 account of Mike Dowe — a former POW who served with Father Kapaun — in The Saturday Evening Post.

“It just amazed me,” Ray recalled. “I saw what he did. What he was. How they felt about him.”

In Hawaii, he visited the Punchbowl Crater where his uncle had lain for more than 60 years.

“Someone asked me if I was upset, because he was out here all this time,” Ray Kapaun said while interviewed at the cemetery. “And I said, ‘Just look at where we’re standing. He was out here with all his buddies.’”

But he could also imagine the priest saying, “Take me back to Kansas.”

The whole return trip was an epic homecoming.

Everywhere, from the laboratory in Hawaii to the streets and Catholic church in Father Kapaun’s hometown of Pilsen, people paid their respects as his body made its way to a final resting place in Wichita’s cathedral. Among those who came were several former POWs whose lives were changed by Father Kapaun.

Herbert Miller, one of many soldiers whose life Father Kapaun saved on the battlefield, was the only one named in the chaplain’s 2013 Medal of Honor citation. The citation read, in part: “Shortly after his capture, Chaplain Kapaun, with complete disregard for his personal safety and unwavering resolve, bravely pushed aside an enemy soldier preparing to execute Sergeant First Class Herbert A. Miller.”

The stunned enemy soldier watched the chaplain lift the wounded Miller on his back and carry him away. Miller later told reporters, “Why that man never shot him, I’ll never know.”

Seventy years later, Miller, Mike Dowe and other POWs — by this time in their 90s — traveled to Kansas for Father Kapaun’s funeral Mass and burial at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Wichita on Sept. 29, 2021.

They will never forget the opportunity to spend time privately in the presence of their beloved chaplain’s remains.

Dowe, who is a member of St. Ignatius Loyola Council 10861 in Spring, Texas, had advocated for decades that Kapaun be awarded the Medal of Honor. He was present for the 2013 White House ceremony, but never did he imagine he would ever attend the priest’s funeral.

“We were there with the corpse before the funeral. And they opened the casket and allowed us to touch the remains of Father Kapaun,” Dowe recalled. “That was a very emotional moment.”

The priest who carried them had finally been carried home.

*****

TOM HOOPES is vice president of college relations at Benedictine College and a member of Sacred Heart Council 723 in Atchison, Kan.

©2024 Texas State Council. All rights reserved.

6633 Hwy 290 East, Ste 204 Austin, TX 78723